There were many ways to resist the British Empire in India, some chose the street, others chose the jail, some chose the slogan and the crowd. But Tej Bahadur Sapru chose something far quieter, and far more difficult.

He chose the law.

At a time when the Empire ruled India through statutes, ordinances, and courts, Sapru believed that the same law could be used to restrain power. He did not believe in noise, he believed in arguments, he did not believe in spectacles as he believed in reasons. History often remembers those who shook the ground; it sometimes forgets those who steadily weakened the foundations, and Tej Bahadur Sapru was one of them.

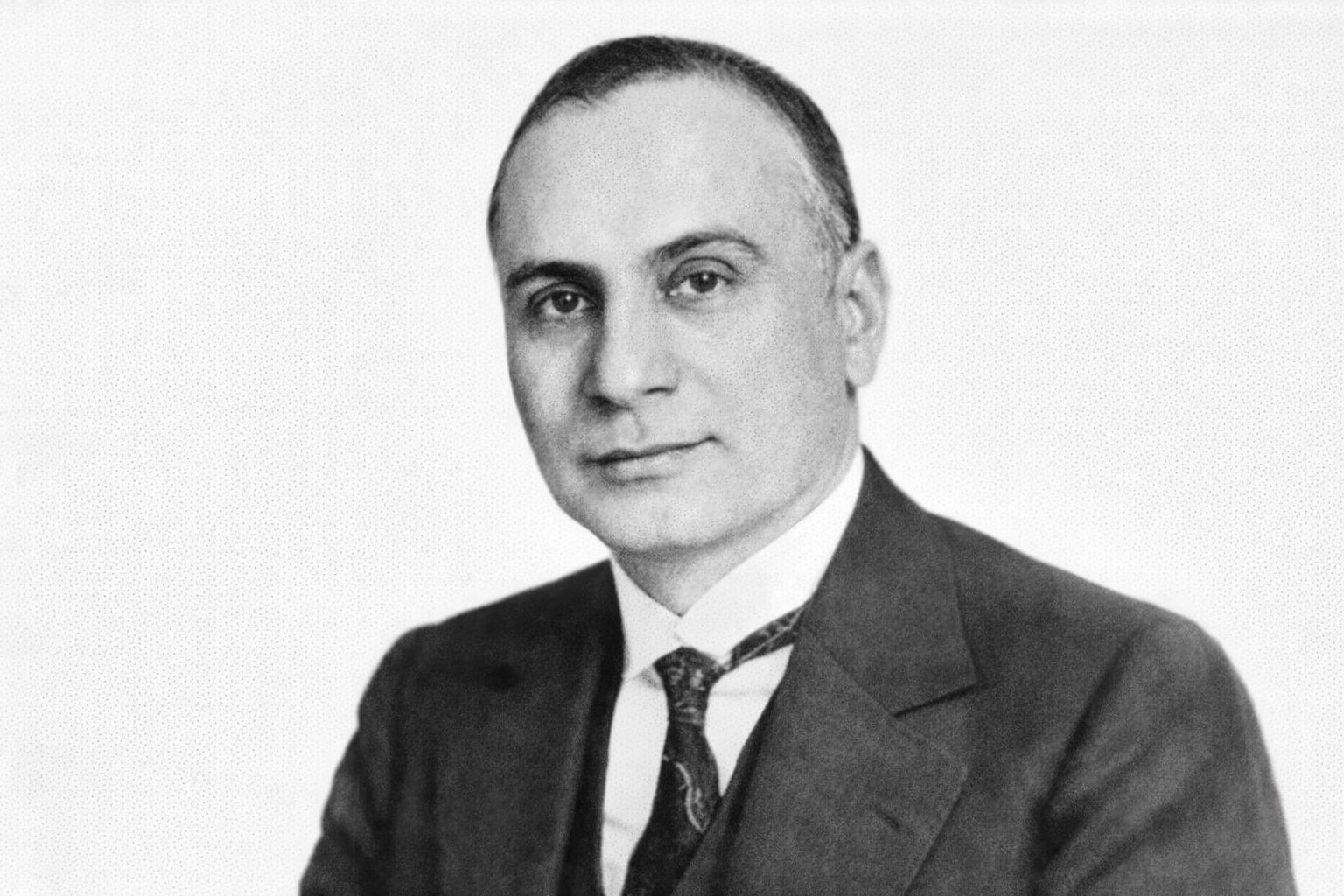

He was born in 1875 in Aligarh, in the United Provinces, Tej Bahadur Sapru grew up in an India where British authority was firm and unquestioned. His family valued education, and Sapru was trained early to think clearly, speak precisely, and argue carefully. These qualities would later define his life.

He studied law in England and was called to the Bar at the Inner Temple. When he returned to India, he entered legal practice not as a fiery nationalist, but as a serious constitutional lawyer. In the colonial courts, he quickly gained a reputation for intellectual clarity and restraint. Judges listened when Tej Bahadur Sapru spoke, not because he raised his voice, but because his arguments were difficult to dismiss.

Tej Bahadur Sapru understood something that many have overlooked. The British Empire did not govern India only through force instead it governed through procedure, legality, and claims of moral authority. Every law it passed, every court it ran, was meant to show that British rule was rational and just. Tej Bahadur Sapru decided to challenge the Empire on its own chosen ground.

He believed that arbitrary power could be exposed if one insisted, relentlessly, on due process, civil liberties, and constitutional limits. This belief shaped his entire public life. As colonial repression increased, especially after the First World War, Tej Bahadur Sapru became deeply concerned with the erosion of civil rights. Laws allowed detention without trial; press freedoms were curtailed; public assemblies were not allowed. Many accepted these as unavoidable facts of colonial rule, but Tej Bahadur Sapru did not. He argued that if the British claimed to rule India by law, then the law must protect Indians as well. Otherwise, the Empire stood exposed to contradiction. In courtrooms, commissions, and public forums, he insisted that legality without justice was not legal at all.

Tej Bahadur Sapru was often described as a “moderate.” The word has not been kind to his memory. Over time, it came to suggest weakness, compromise, or lack of courage. But Tej Bahadur Sapru’s moderation was not soft, it was discipline. He refused easy applause; he refused slogans that could not be defended in law. Tej Bahadur Sapru refused violence not because he lacked anger, but because he believed that violence would allow power to escape accountability. For Tej Bahadur Sapru, the restraint was not submission; it was a strategy.

This approach placed him in a difficult position as nationalists who favored mass agitation saw him as too cautious. British officials, though respectful of his intellect, were wary of his persistence. Sapru fully belonged to neither camp which meant isolation, limited influence, and fading public recognition, but he continued.

Tej Bahadur Sapru played a significant role in constitutional discussions in the years after the First World War, when India’s future was being debated. He participated in the Round Table Conferences in London, where India’s future governance was debated. These conferences are often dismissed as failures in popular history, but that assessment ignores their constitutional significance.

Tej Bahadur Sapru did not attended them expecting instant freedom instead he attended them to place legal limits on imperial power, to record Indian objections, and to put constitutional questions into the open. He believed that even when power refused to concede, arguments placed on record had lasting force. In London, Tej Bahadur Sapru argued that India could not be governed indefinitely through emergency powers and discretionary authority. He pressed for civil liberties, responsible government, and legal safeguards. He spoke not as a rebel, but as a jurist confronting an empire with its own principles.

This was dangerous work in its own way. To accept constitutional discussion was, for many nationalists, to legitimize colonial rule and to push too hard was to threaten imperial control for the British. Tej Bahadur Sapru walked this narrow line deliberately. He believed that freedom would not survive without institutions strong enough to protect it. Courts, legislatures, and constitutional conventions mattered to him not as symbols, but as safeguards against future abuse of power, whether foreign or domestic.

Unlike many leaders of his time, Tej Bahadur Sapru was thinking beyond independence. He worried about what would happen after the British left. Would India replace one arbitrary authority with another? Would power simply change hands, or would it be restrained by law? These concerns made him deeply relevant, even when he seemed unfashionable.

Tej Bahadur Sapru’s legal philosophy rested on a simple but demanding idea: that the rule of law must bind rulers as firmly as it binds citizens. This idea brought him respect from the judiciary and suspicion from the executive. It also placed him among those lawyers who saw freedom not as an event, but as a system.

He did not leave behind dramatic prison stories or iconic slogans. What he left behind was: arguments, memoranda, dissenting positions, and constitutional principles. These are harder to celebrate, but easier to build upon. As the freedom movement moved closer to its goal, Tej Bahadur Sapru’s influence began to fade from public memory as louder voices dominated the narrative. Yet many of the constitutional ideas that later shaped independent India echoed concerns Sapru had raised years earlier.

He lived long enough to see independence, but not long enough to shape the Constitution directly. Still, his insistence on civil liberties, judicial independence, and constitutional restraint formed part of the intellectual soil in which the Republic was planted.

In remembering Tej Bahadur Sapru, we are reminded that not every act of courage is loud. Some forms of resistance take place across tables, inside courtrooms, and within carefully chosen words. Tej Bahadur Sapru fought the Raj without raising a slogan. He fought it by refusing to let power escape the discipline of law. In doing so, he showed that freedom is not only won by protest but it is preserved by principle.

As we continue this journey through the lawyers of India’s freedom struggle, Tej Bahadur Sapru stands as a reminder that the quiet insistence on legality can be as revolutionary as the loudest cry for change.

Next, we turn to another courtroom, another advocate, and another way in which law was used to challenge empire because we all know that the story of freedom was never written in one voice.